Revil Unravelled

Published on 01 Sep 2020 | Updated on 01 Sep 2020

CyberSense is a monthly bulletin by CSA that spotlights salient cybersecurity topics, trends and technologies, based on curated articles and commentaries. CSA provides periodic updates to these bulletins when there are new developments.

The Sodinokibi (also known as REvil) ransomware has quickly gained notoriety since its discovery in April 2019, having a significant number of high-profile hits across multiple sectors in a relatively short span of time. Just like how IT developers update software and improve them over time, Sodinokibi developers have continually upgraded the ransomware strain to increase its threats.

A study by cybersecurity firm Coveware noted that Sodinokibi ( alongside Maze, covered in the May 2020 issue of Cybersense) was among the most prevalent ransomware strains in Q1 2020[1]; this coincided with the period when cyber threat actors were capitalising on economic and workplace disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic for nefarious purposes. In fact, Sodinokibi’s infamy was already gaining ground since its emergence; the threat actors behind Sodinokibi were suspected to be the same group behind the GandCrab ransomware, with the latter reportedly accounting for about 40% of the global ransomware market at the height of its prominence.[2] This issue of Cybersense takes a closer look at this novel and fast-growing menace.

Figure 1: Diamond Model for Sodinokibi ransomware

NOTABLE CHARACTERISTICS

Ransomware as a Service

Sodinokibi operates through a Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) model.[3] RaaS predicates on having developers in charge of maintaining the ransomware code, while another group – called affiliates – is responsible for spreading the ransomware. The malware strains are typically marketed for sale on dark web forums. As such, the barrier of entry is relatively low, as individuals with limited technical skills may access the ransomware through criminal networks to distribute the malware.

Intrusion Vectors

The RaaS model provides tools that enable the affiliates to distribute the ransomware through an array of methods, such as brute force attacks, exploiting insecure Remote Desktop Protocols (RDPs) or unpatched Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), and spam campaigns. A common method of propagation is through phishing e-mails or malicious advertising[4], whereby threat actors utilise social engineering to lure victims into clicking malicious links that download the malware into their systems. A most recent addition to Sodinokibi’s arsenal of intrusion techniques allows its affiliates to target victims through credit card or Point of Sale (POS) software compromises.[5]

Obfuscation Techniques

Sodinokibi leverages a range of obfuscation techniques to evade detection. For example, the ransomware is designed in such a way that it does not have a readable string (i.e. more difficult to identify). In addition, the malicious codes may be embedded inside a zipped file, which generally has a low detection rate by anti-virus systems.[6]

Post-compromise Strategies

Since early 2020, cybercriminals behind Sodinokibi have adopted the “name and shame” strategy, by threatening to publicly-release the names of victims who refused to accede to ransom demands. The strategy was pioneered through the Maze ransomware, and increasingly adopted by other ransomware gangs, given its effectiveness in coercing victims to pay up the ransom. Sodinokibi cybercriminals have even launched their own website named “Happy Blog” where they would post samples of stolen data as proof of possession, and threaten its release to the public.[7] In addition, there had been observations of these stolen data being put up for auction on dark web markets. Such a strategy could be highly lucrative, especially when the stolen data pertains to a high-profile victim, or if it contains classified commercial information that may be valued by competitors.Notable Sectors Targeted

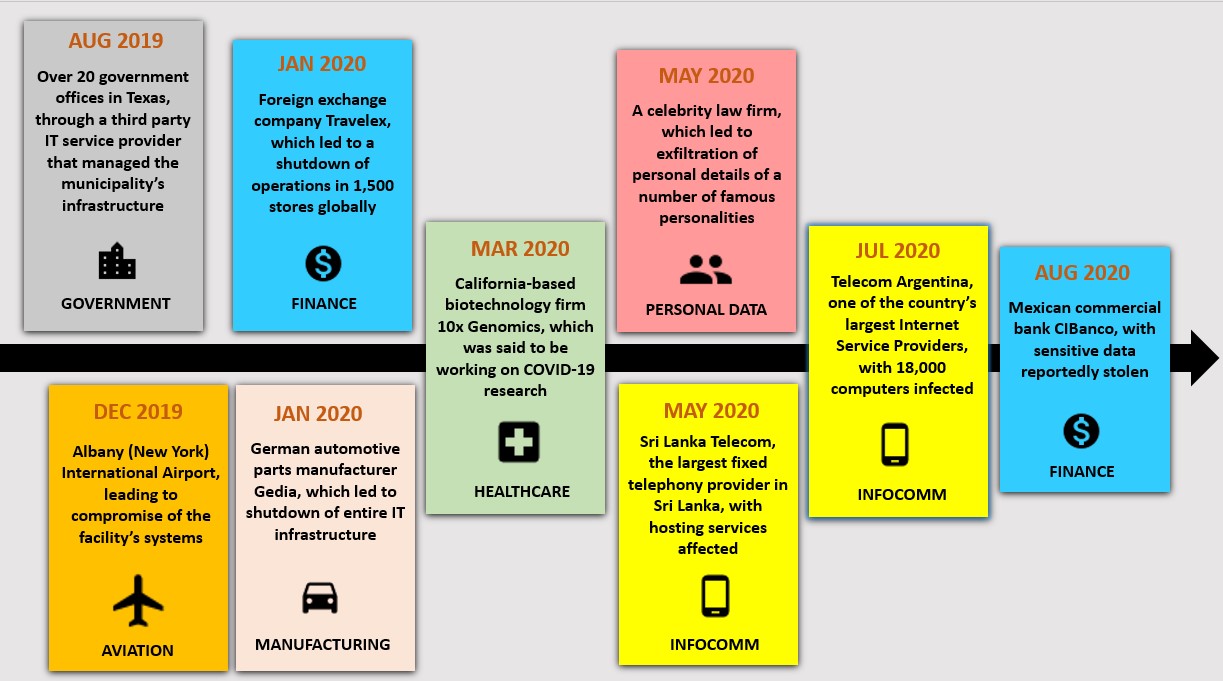

The Sodinokibi ransomware has inflicted harm on organisations across many sectors since its emergence. Its victims have spanned a myriad of sectors including government, healthcare, infocomm, and finance. While most of its victims are located in US, organisations elsewhere in the world have also fallen prey.

Figure 2: Timeline of notable hits by Sodinokibi from August 2019 to date

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Ransomware will continue to pervade, especially when driven by the profitable nature of such attacks amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has inevitably increased the attack surface as individuals and businesses are forced to adapt new technologies rapidly to maintain business continuity. A ransomware attack can have devastating outcomes for affected organisations; in many cases, it could mean operational downtime, data loss or even intellectual property theft.

Ransomware attacks rose by 25% in Q1 2020 compared to Q4 2019[8], and the impact that Maze and Sodinokibi had on organisations is palpable. Both ransomware strains have afflicted numerous organisations across sectors, and the cybercriminals behind both groups have evolved their tactics (such as through the “name and shame” strategy) to increase the chances of ransom payouts. It is conceivable that threat actors will continue to think of innovative ways to exploit their victims, and the threats posed by ransomware warrants extra caution and vigilance.

References

- [1] Ransomware Payments Up 33% as Maze and Sodinokibi Proliferate in Q1 2020

- [2] Following in GandCrab’s Big Footsteps, Sodinokibi is Storming Organizations

- [3] McAfee ATR Analyzes Sodinokibi aka REvil Ransomware-as-a-Service – What The Code Tells Us

- [4] An Analysis of Sodinikibi: The Persistent Ransomware as a Service

- [5] Sodinokibi Now Scans Networks for POS Systems

- [6] Taking Deep Dive into Sodinokibi Ransomware

- [7] REvil Ransomware Starts Auctioning Victim Data

- [8] Ransomware Threats Surge by 25% in Q1 2020: Report