The Evolution of Cyber Futures and its Key Drivers

9 June 2020

CyberSense is a monthly bulletin by CSA that spotlights salient cybersecurity topics, trends and technologies, based on curated articles and commentaries. CSA provides periodic updates to these bulletins when there are new developments.

For nearly 50 years, the practice of futures thinking has helped organisations and countries identify opportunities and potential hazards more quickly. While it is often confused with crystal-ball gazing and predicting “what-happens-next?”, futures thinking and strategic foresight should rather, be seen as efforts to illustrate the potential trajectories and unexpected implications of contemporary issues, through the development of possible scenarios.

Unsurprisingly, Cyberspace – given its complexity, inter-dependencies and constant evolution – has proven to be a fertile ground for the application of futures thinking and strategic foresight. This issue of Cybersense provides a broad history of the evolution of ‘cyber futures’, and looks at some important drivers in its ongoing development.

Mid-Late 2000s – Cyberspace as an extension of Geopolitics

The noughties can be considered a watershed for cyber futures - at the turn of the millennium, optimism was widespread over the potential of the Internet for knowledge-sharing, e-commerce and the provision of amenities and services online. Yet this view would change considerably by the end of the decade, as the world witnessed two potent demonstrations of the destructive potential of cyberspace. The first, in 2007, saw Estonia brought to its knees by a series of cyberattacks that targeted the country’s web infrastructure. The following year, Georgia came under massive, sustained Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks that disabled the country’s Internet access during the Russo-Georgian War – notable for also being the first-ever use of cyber-attacks in conjunction with a physical conflict. In both instances, the damage caused was serious, extensive, and required years to restore. It was clear by then that the cyber-genie was out of the bottle.

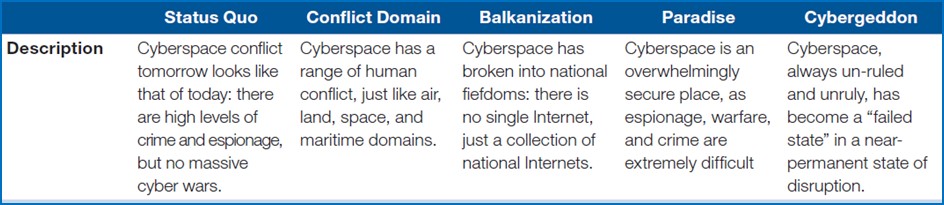

While the possibility of cyber-attacks being able to affect physical domains – to the extent of crippling governments and entire economies - was mooted as early as 2000, these ideas only really began gain serious traction after Estonia and Georgia. At around the same time as these two events, conflicting geopolitical interests over control of Cyberspace manifested roughly as two rival coalitions – the Western countries on one hand, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (comprising Russia, China, and their central-Asia allies) on the other. A sense of realism pervaded the work of Cyber-futurists and scenario planners. American think-tank The Atlantic Council captured this more complex outlook with their seminal “The Five Futures of Cyber Conflict and Cooperation” (2011), establishing some fundamental trajectories for the development of Cyberspace:

Figure 1. Summary of the Five Futures of Cyber Conflict and Cooperation (Atlantic Council, Dec 2011)

These scenarios were similar to those envisaged in other foresight pieces of the time (including MIT’s 2012 ‘Cyberpolitics in International Relations’) with most of them varying on the formulaic inputs established by Five Futures, namely the extent of international cooperation/ conflict and degree of national control over the Internet. ‘Balkanization’ (also known as the ‘Garrison Internet’) - where Cyberspace is divided into subnets controlled by different states or cyber-coalitions – was noted for its relevance, and has been refined into other scenarios including ‘Bifurcation’, reflecting contemporary US-China tensions.

Read more about the Atlantic Council’s latest Alternate Cybersecurity Futures (2019) here.

Late 2000s – Here comes the new challengers

Countries, however, are not the only actors in Cyberspace, and indeed, are often unable to exercise the same kinds of powers in the virtual world as they do within their jurisdictions. By the 2010, it gradually became clear that major tech firms like Google, Facebook, Apple, and Amazon – as a result of their dominance over online activity and the enormous amounts of data they collect – were emerging as the new ‘sovereigns’ of the virtual world.

The power wielded by the tech corporations and other non-state actors within the Internet was posited as an important driver in the cyber futures envisaged during this period, influenced in part by instances of Big Tech pushbacks against legislation (such as Google’s contention against European countries over the ‘right to be forgotten’ online). The Zurich Insurance Group’s ‘Risk Nexus: Overcome by cyber risks?’ (2015) articulated an Independent Internet scenario as such: “The technological elite defy the state and continue to invent new ways to outfox regulations, laws, and other constraints of the state, such as refusing requests for government backdoors.” The interest over the developing role of tech giants in Cyberspace would be continually refined through several other foresight pieces, including ‘Barlow’s Revenge’ - which envisaged parts of the world ceding effective control of Cyberspace to tech corporations - in UC Berkley’s Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity (CLTC) and the World Economic Forum’s “Cybersecurity Futures 2025” project (2019).

Read more about the CLTC and WEF’s Cybersecurity Futures 2025 here .

Figure 2. Scenario summary of Barlow’s Revenge (Cybersecurity Futures 2025)

Mid-2010s – The Tech Genie’s out of the Bottle

Beyond state and non-state actors, the 2010s would witness the advent and progress of advanced technologies poised to reshape or drastically alter the cyber landscape. Their integration into all aspects of daily life and activity have created new opportunities, but also vulnerabilities and security concerns. These technologies include Artificial Intelligence, Quantum computing, 5G cellular technology and the Internet-of-Things (IoT), each highly impactful in their own right, but game-changers for cybersecurity, data privacy and Internet surveillance, to name but a few.

The double-edged nature of these technologies was examined in a number of influential reports. The CLTC’s ‘Cybersecurity Futures 2020’ (2015) reflected concerns over how technological breakthroughs far outpaced protective cybersecurity measures and legislation, and portrayed a number of dystopian futures where AI, IoT and Smart Technologies were employed for less than noble purposes. The impact of these technologies on cybersecurity would continue to be the focus in the follow-up ‘Cybersecurity Futures 2025’, which posited trajectories based on the potential ways that these technologies and other drivers can interact to create unexpected outcomes.

Figure 3: The Five Scenarios from UC Berkley CLTC’s Cyber Futures 2025

Present – The Future is Now?

In early 2020, the CLTC looked back at the scenarios they developed five years ago and reflected on the driving forces that they either underestimated or failed to account for. The most important of these was not some new technology or emerging trend, but rather, how strongly traditional geopolitics – despite the advent of the new actors and technologies – have continued to shape Cyberspace. What is different though is how states have leveraged, or interacted with other cyber drivers and contemporary trends to achieve their aims.

Being premised on contemporary issues, the only thing that can be definitively said about Cyber futures is that the discipline will become even more complex, moving forward. The interplay between cybersecurity and several related topics or ‘adjacencies’ that have emerged in the last few years – information and influence operations, fake news, etc. adds new dimensions and dynamics to the question of how Cyberspace may yet develop. As a prediction tool, futures thinking is certainly far from accurate; but as the CLTC aptly notes in its post-mortem of the 2015 scenarios, “[Cyber futures can still] help us learn about the evolution of the cybersecurity world by assessing what kinds of causes and implications we saw clearly, and more importantly, what we failed to forsee and why.”

Read more about CLTC’s Post Morterm on Cyber Futures 2020 here.

Figure 4: The Future of Cybersecurity? (Copyright: Mike Smith, Las Vegas Sun, 2019)

SOURCES INCLUDE:

The Atlantic Council, The Centre for Long Term Cybersecurity, Medium, and the World Economic Forum